Detroit's mass-production know-how yielded over 55,000 Merlin V12 aircraft engines during WWII. But were they better than the ones built in Britain?

By Graham Kozak, originally published in Autoweek

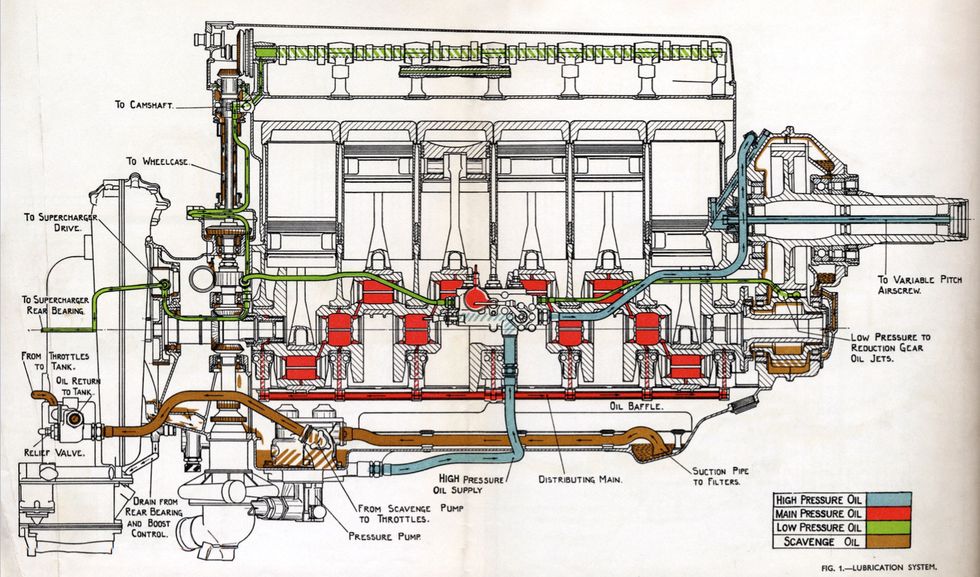

The saga of the Roll-Royce Merlin V12 supercharged aircraft engine is one of the most gripping engineering and manufacturing stories of the 20th century. Here was an incredibly complex piece of machinery, conceived before the clouds of World War II gathered and continuously refined in the pressure cooker of combat, that would go on to power some of the most unforgettable piston-driven warplanes ever designed—the Supermarine Spitfire and the P-51 Mustang among them.

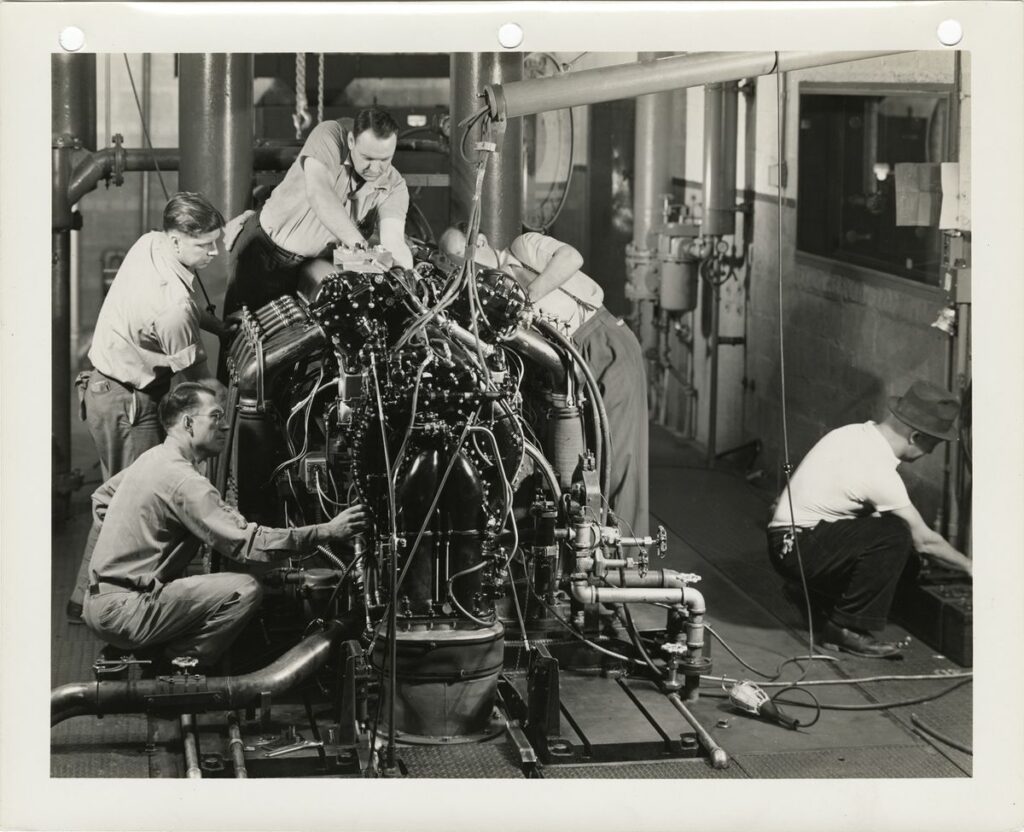

And at the center of its story are two great automotive marques, Rolls-Royce and Packard, which built Merlins by the tens of thousands simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic.

If you have even a passing interest in automotive, aviation or military history, you’ve probably heard some variation of the Merlin tale. The received wisdom, at least in America, usually runs along the lines of: If Rolls-Royce birthed a stupendous engine, Packard brought American mass-manufacturing know-how to the equation, perfecting the design and mechanizing production. And so the Axis powers were beat back by this perfect transatlantic alliance of British ingenuity and American industrial might.

There are many variations on this basic storyline, more than a few of which are contradictory. Most recently, I was told very matter-of-factly (and by a Brit, if that makes any difference) that Rolls built a more precisely fitted, finely tuned engine that had slightly higher performance potential for a given unit. Packard, by contrast, built one that was ultimately easier to construct consistently and overhaul at specified intervals—and that one of the ways Packard accomplished this was by building Merlins with looser tolerances than its counterpart on the other side of the Atlantic.

There’s an appealing counterintuitiveness to the notion that a (marginally) sloppier engine makes for a more effective fighter plane powerplant; it’s a bit like that chestnut about adding armor to the parts of the bombers with no bullet holes. Blueprinted, handmade and expertly tuned Merlins might have been nice to have under ideal circumstances, but WWII demanded materiel in almost unfathomable quantities. On the surface, it’s conceivable that two pretty good Detroit-built Merlins were worth one exquisite Merlin handcrafted in Crewe.

On the other hand, I’ve also read that Packard’s cutting-edge manufacturing methods made for Merlins with tighter, more consistent tolerances. Both of these cannot be true. Or can they?

Since Autoweek is talking tolerance this week, it seemed like an opportune time to dig a little deeper into the Merlin story—which, after all, is a big point of pride for Packard car owners like myself. I can only imagine Rolls-Royce owners look back on this period of history with equal admiration.

But much like Abraham Wald’s WWII-era work on aircraft survivability, it’s tough to say exactly how much of this neatly packaged story is nothing more than enticing elaboration spun around just a few spindles of fact.

From this modern vantage point, it might seem inevitable that Rolls-Royce would join forces with Packard to produce Merlins. Rolls-Royce Limited was established in 1904; the Packard Motor Car Co. was founded in Warren, Ohio, a few years earlier, in 1899, and set up shop in Detroit in 1903. Both built their global reputations as top-level luxury automakers on the strengths of their engineering expertise and high production standards.

As WWII approached, both companies had extensive experience with aircraft engines under their respective belts. Packard’s early efforts resulted in the successful Liberty V12, which arrived several months after the United States’ April 1917 entry into World War I. Rolls-Royce began producing its Eagle V12 in early 1915, also to power warplanes; it started development of the PV-12, the engine that would become the Merlin, in the early 1930s and had running prototypes by 1933.

The first “production” version of the engine was the Merlin I, which arrived in 1936, but fewer than 200 examples were built. The Merlin II was developed about a year later, and from there it was off to the races: A dizzying number of variants would follow in quick succession.

Engineering refinements meant that by the end of the war, the Merlin 66, an intercooled variant of the engine sporting a two-stage, two-speed supercharger, was making 2,050 hp (increased from 1,030 hp in the Merlin II)—and these improved engines were allowing aircraft to operate at significantly higher altitudes, as well. If you want to dive into the minutiae of Merlin development, it’s worth grabbing a copy of The Merlin in Perspective—The Combat Years, by Alec Harvey-Bailey; there’s simply too much info to relate it all here.

Packard had investigated the prospect of building Merlins under license as early as 1938. Though these initial discussions went nowhere, the British declaration of war on Germany in September 1939 meant that a new manufacturing partner was urgently needed.

Ancillary production of the Merlin might have gone to a different American automaker entirely, however, if not for its mercurial founder and namesake. In 1940, Ford Motor Co. initially committed to build 9,000 Merlin engines—6,000 for the British and 3,000 for the American armed forces—in mid-1940, over a year before the United States entered the conflict. The company even went so far as to take delivery of Rolls-Royce blueprints and an example engine before Henry Ford suddenly and controversially backed out of the deal, asserting that his company would not supply materiel to any foreign powers involved in conflict. (A.J. Baime relates this incident, and the detrimental effect it had on Edsel Ford, inThe Arsenal of Democracy: FDR, Detroit, and an Epic Quest to Arm An America at War.